Safety and risks associated with screening for chromosomal abnormalities during pregnancy

Bezpečnost a rizika spojená se screeningem chromozomálních abnormalit během těhotenství

Cíle:

Stanovení rizika a bezpečnosti screeningu chromozomálních abnormalit během těhotenství prostřednictvím posouzení ultrazvukové expozice a četnosti úmrtí plodu po trans-abdominální aminocentéze (AMNIO) nebo odběru choriových klků (CVS).

Metody:

Metodou je retrospektivní analýza četnosti úmrtí plodu po provedení AMNIO a CVS jako diagnostického testu chromozomálních aberací během těhotenství (1391 pacientek s jednočetným těhotenstvím, které navštívily naši kliniku v období od ledna 2005 do prosince 2009 – 1038 AMNIO vyšetření a 353 CVS vyšetření). Těhotné byly sledovány pro zjištění četnosti úmrtí plodu po provedení vyšetřovací metody definovaného jako intrauterinní zánik nebo potrat před 24. týdnem těhotenství. Na základě přehledu literatury byla posuzována bezpečnost ultrazvuku během těhotenství.

Výsledky:

Ve skupině CVS bylo toto vyšetření v 86 % provedeno na základě pozitivního screeningu (screening chromozomálních abnormalit na bázi měření nuchální translucence a markerů v biochemickém séru (PAP-A and beta-HCG)). Střední věk rodiček 31,7 let a četnost potratu 0,6 %. Ve skupině AMNIO bylo vyšetření provedeno na základě pozitivního triple testu v druhém trimestru (screening chromozomálních abnormalit na bázi měření markerů v biochemickém séru, alpha-fetoproteinu, estriolu a celkového HCG v druhém trimestru těhotenství). Střední věk rodiček 33,2 let a četnost potratu 0,8 %. Přehled literatury ukazuje, že vzhledem k omezenému množství dostupných informací o některých faktorech (gestační věk, délka a počet expozicí ultrazvuku) během těhotenství by měl být pacient k získání požadovaných diagnostických informací vystaven co nejnižším působením ultrazvukové energie.

Závěr:

Četnost úmrtí plodu v naší studii potvrdila, že riziko obou vyšetřovacích metod je srovnatelné (0,8 % pro AMNIO a 0,6 % pro CVS). Nižší četnost potratovosti po CVS může být vysvětlena teorií, kdy je placenta brána jako houbovitý orgán, který svůj tvar zachovává snadněji při vykonání vyšetřovací metody umožňující snazší hojení, než když vyšetřovací jehla prochází přes amnion, který je již tak roztažený plodovou vodou. Jsme si však vědomi příliš malou velikostí zkoumaného vzorku. Podle dostupných důkazů se tak diagnostická ultrasonografie v průběhu těhotenství jeví jako bezpečná.

Klíčová slova:

četnost úmrtí plodu, odběr choriových klků, amniocentéza, bezpečnost ultrazvukového vyšetření v ěhotenství.

Authors:

I. Dhaifalah 1; J. Zapletalová 2

Authors‘ workplace:

Department of Genetic and Fetal Medicine, University Hospital, Olomouc, Czech Republic

1; Department of Medical Biophysics, University Hospital, Olomouc, Czech Republic

2

Published in:

Ceska Gynekol 2012; 77(3): 236-241

Overview

Objectives:

To assess the risk and safety of screening for chromosomal abnormalities during pregnancy through the assessment of exposure to ultrasound and the fetal loss rate after trans-abdominal amniocentesis (AMNIO) or chorionic villus sampling (CVS).

Methods:

It is a retrospective analysis of the fetal loss rate following AMNIO and CVS as a diagnostic tests for chromosomal abnormalities during pregnancy in 1391 singleton pregnancies who attended our clinic from January 2005 to December 2009 (1038 AMNIO and 353 CVS). Pregnancies were followed up to ascertain the fetal loss rate after the procedure which was defined as intrauterine demise or miscarriage before the 24th week of gestation. Review of literature was the method used for assessing the safety of ultrasound during pregnancy.

Results:

In the group of CVS about 86% of the cases were referred because of a positive screening (screening of chromosomal abnormalities on the bases nuchal translucency and biochemical serum markers (pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin)), test with mean maternal age of 31.7 years and a miscarriage rate of 0.6%. In the group of AMNIO, 40% of the cases were referred because of a positive triple test in the second trimester (screening of chromosomal abnormalities on the bases of biochemical serum markers, alpha-fetoprotein, estriol and total human chorionic gonadotropin in the second trimester of pregnancy). Mean maternal age of 33.2 years and a miscarriage rate of 0.8%. The review of the literature indicates that due to limited amount of information available on some factors (gestational age, duration and number of exposure) during the pregnancy the patient should be exposed to the least ultrasound energy necessary to obtain desired information.

Conclusion:

The fetal loss rate in our study had confirmed that the risk of both procedures is comparable and is 0.8% for AMNIO and 0.6% for CVS. The lower miscarriage rate after CVS could be explained by the theory that placenta is a spongy organ that will expand easily after the procedure allowing better healing than if the needle had been passed through the amnion which is even more stretched by the amniotic fluid, but we are a wear of that the sample size is too small for such a conclusion. According to the available evidence, exposure to diagnostic ultrasonography during pregnancy appears to be safe.

Key words:

fetal loss rate, chorionic villus sampling, amniocentesis, safety of ultrasound during pregnancy.

INTRODUCTION

There are two key safety issues relating to screening of chromosomal abnormalities during pregnancy that need to be considered. These relate to the use of ultrasound in pregnancy and follow-up diagnostic (AMNIO/CVS) procedures.

The literature focusing on the safety of ultrasound in pregnancy is scant compared to its widespread use and acceptance, although it is assumed that major adverse events would have come to light by now. The literature is also not of high quality. However, the wide spread use of the procedure and the fact that no major adverse events have come to light suggests that ultrasound in pregnancy is safe [8].

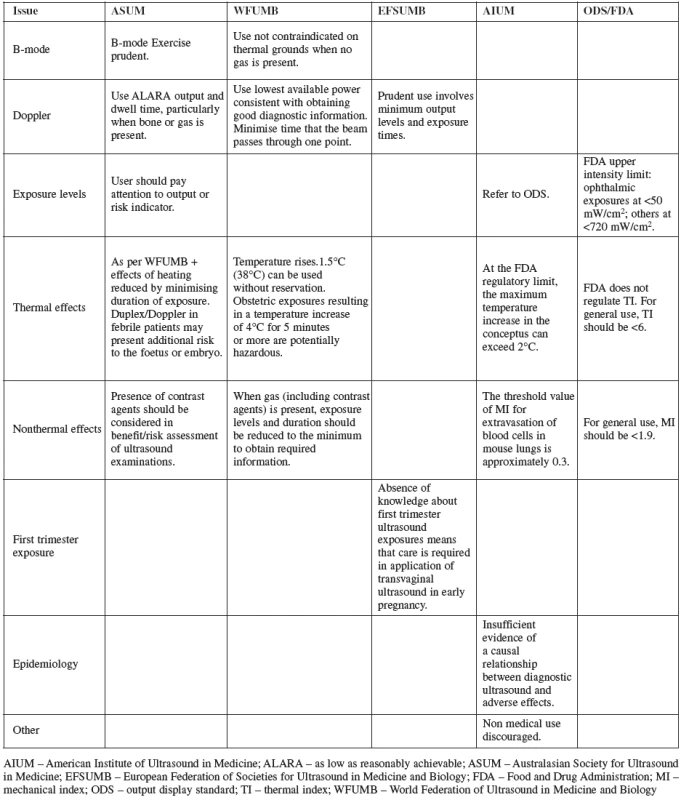

Several professional organizations have issued recommendations about the use aof specific types of ultrasonic imaging methods based on indication, maternal and fetal characteristics and the potential for teratogenic or other adverse outcomes. These support the prudent use of the technology, stressing the importance of minimum output levels and exposure times. Recommendations on the use of ultrasound by the major international organizations are summarized in Table 1 [3].

Most of the available comparative data focusing on AMNIO and CVS are derived from studies conducted in the 1980s. Severe or life threatening adverse events resulting from AMNIO or CVS are extremely rare. However, some publications have reported maternal mortality after such procedures. Transient vaginal spotting or amniotic fluid leakage following AMNIO has been commonly reported as complications. Mostly, both are self-limiting and generally require only reassurance. Following the procedure, there is a 0.5% – 1% risk of spontaneous abortion above the natural background loss rate for a given age of gestation [1, 10].

Studies examining the fetal loss rate associated with CVS are scanty and have inconsistent results. Some of the studies did not find a statistically significant difference in fetal loss rate in women assigned to CVS compared to those receiving AMNIO. CVS is known to be more technically demanding than AMNIO, with a steeper learning curve [2, 9].

Both methods require technical competence in medical and nursing staff. Obstetricians performing the procedure should have adequate training and experience to be able to successfully obtain tissue samples at the initial attempt in about 99% of cases [4, 6, 7].

A systematic review which compared classic AMNIO with CVS using data from three large trials has found differences in maternal complication rates but none were life threatening. Recent data has showed a trend of decreasing laboratory failure rates for both CVS and AMNIO, as well as decreasing rates of mosaicism. Maternal cell contamination rates have also fallen, with this drop attributed to greater experience in the operators providing the samples [4, 5, 11].

METHODS

The cohort consisted of women with singleton pregnancy undergoing AMNIO between 16–20 weeks of pregnancy and CVS between 11–14 weeks of pregnancy at the Fetal Medicine Unit, Institute of Medical Genetic and Fetal Medicine, University Hospital, Olomouc, Czech Republic from January 2005 to December 2009. A total of 1917 women underwent invasive testing either by AMNIO (1522 cases) or by CVS (395 cases). A feedback was obtained in 1038 cases of AMNIO and 353 cases of CVS.

Pregnancy outcome, categorized as elective termination, abortion, stillbirth or live birth was determined by a review of our database, data being collected through data sheets given to the patient before the procedure for return after delivery and or letters to or telephone contacts with the women.

Three operators were performing the AMNIO and two the CVS. AMNIO was performed with a 20 – gauge needle as a sterile procedure under ultrasound guidance. The volume of amniotic fluid withdrawn was 15 to 25 ml. CVS was performed with a 18-gauge needle as a sterile procedure under ultrasound guidance. The amount of chorionic villus collected was about 2–20 mg. We collected data about the indications for the procedures, maternal age and fetal karyotyp from the data base software we use at our unit (Astraia software GmbH, Germany).

We defined fetal loss rate after the procedure as fetal demise or miscarriage before the 24th week of gestation regardless of the cause. Analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0 (SPSS, Inc.) and Statistica 8.0 for Windows (Statsoft, Inc.).

RESULTS

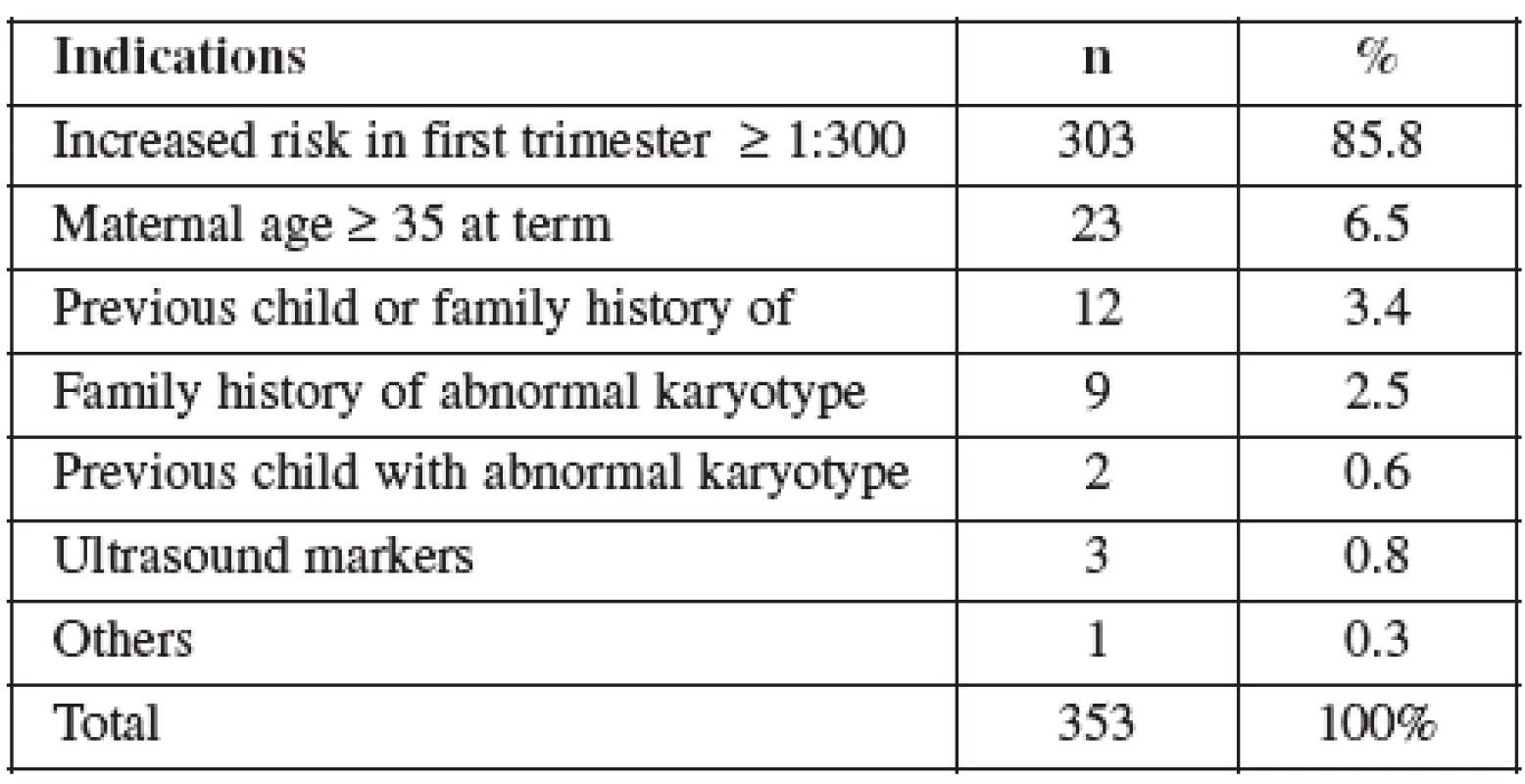

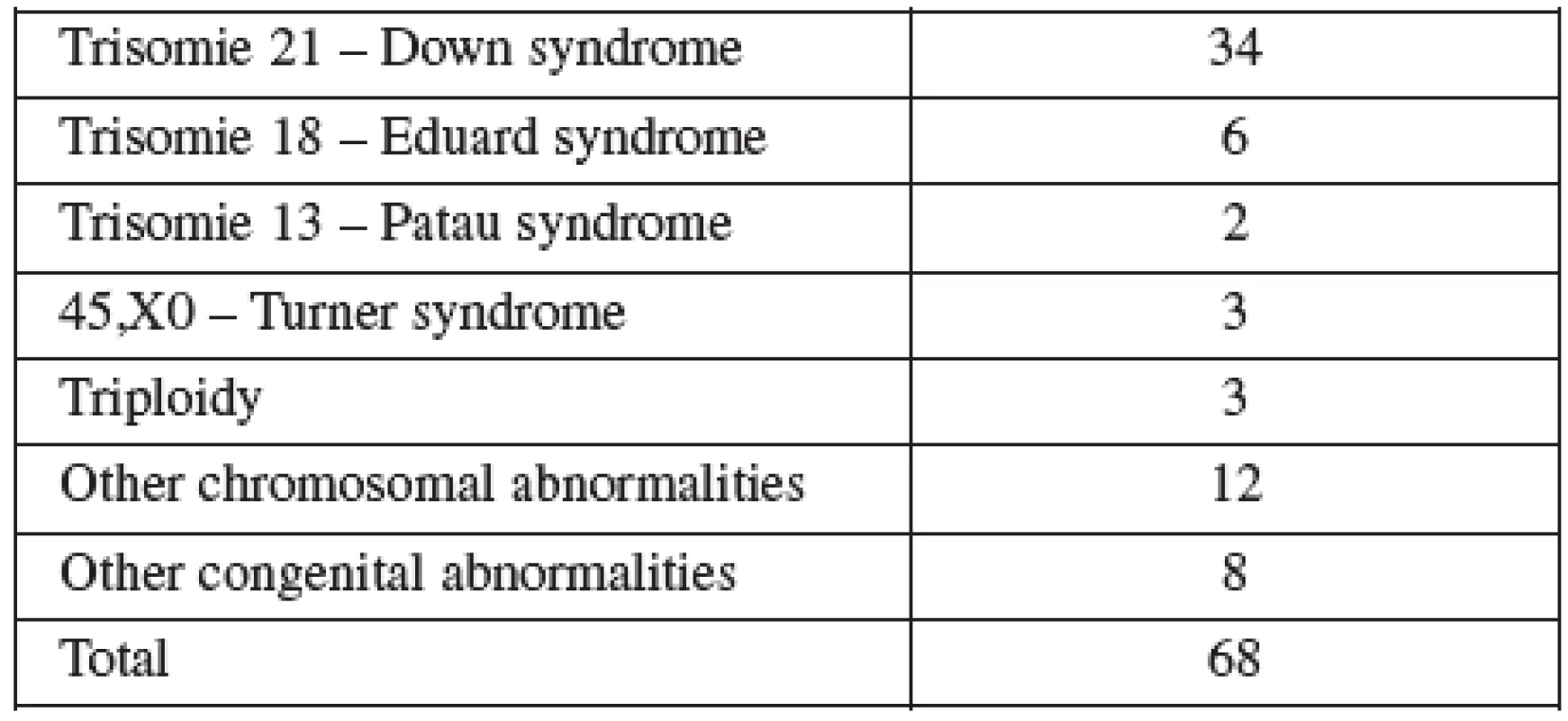

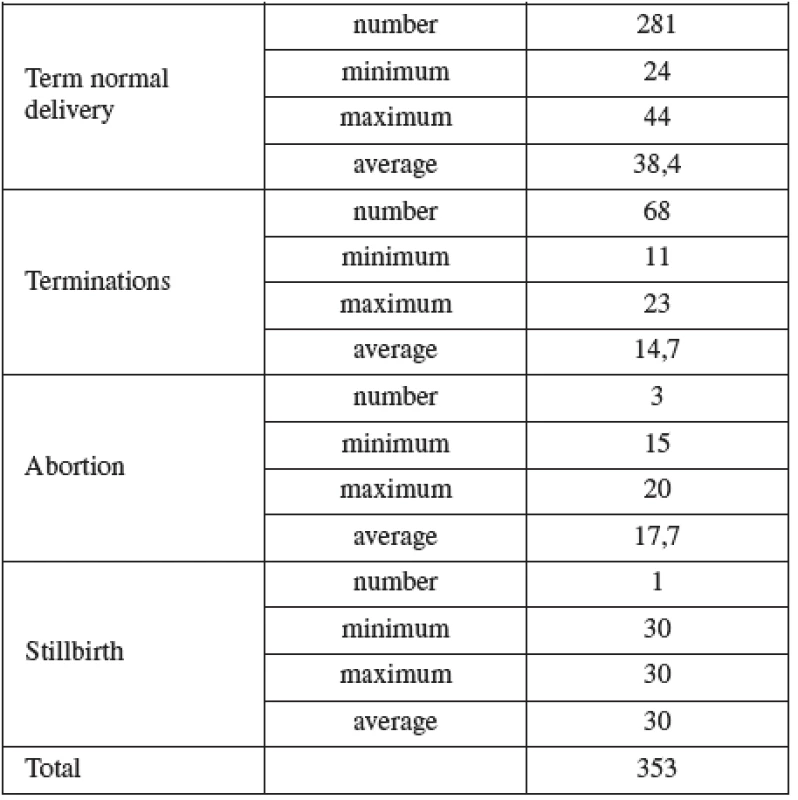

CVS was performed between 11–14 weeks of pregnancy. The main clinical indications in this cohort were positive screening in the first trimester (85.8%) followed by advanced maternal age (6.5%). Mean maternal age was 32 (range 19–46) years. One third of women were older than 35 years. Figure 1 details the distribution of maternal age in this group and Table 2 lists the indications. Normal term delivery occurred in 281 of the cases, 68 pregnancies were terminated for abnormal karyotyp or other abnormality (Table 3) and one case of stillbirth was recorded. There were 3 fetal losses out of the 353 cases, after exclusion of cases lost to follow up. The 3 losses considered to be caused by the procedure occurred at 15, 18 and 20 weeks of gestation giving a 0,6% fetal loss rate for this procedure in our cohort. Table 4 shows detailed follow up.

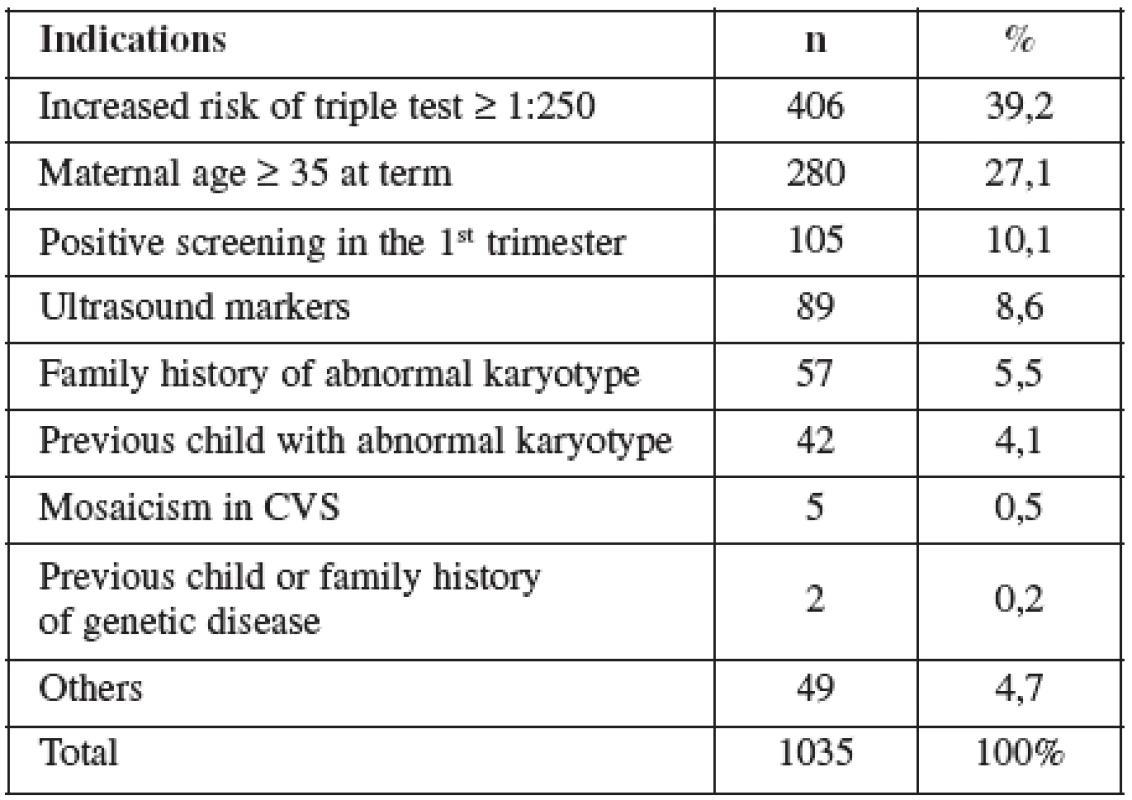

AMNIO was performed between 16–20 weeks of pregnancy. The main clinical indications in this cohort were positive screening in the second trimester by triple test in 39.2%, followed by advanced maternal age (27.1%). Mean maternal age was 33 (range 15–47) years. Forty percent of women were over the age of 35 years. Figure 2 details the distribution of maternal age in this group and Table 5 lists the indications.

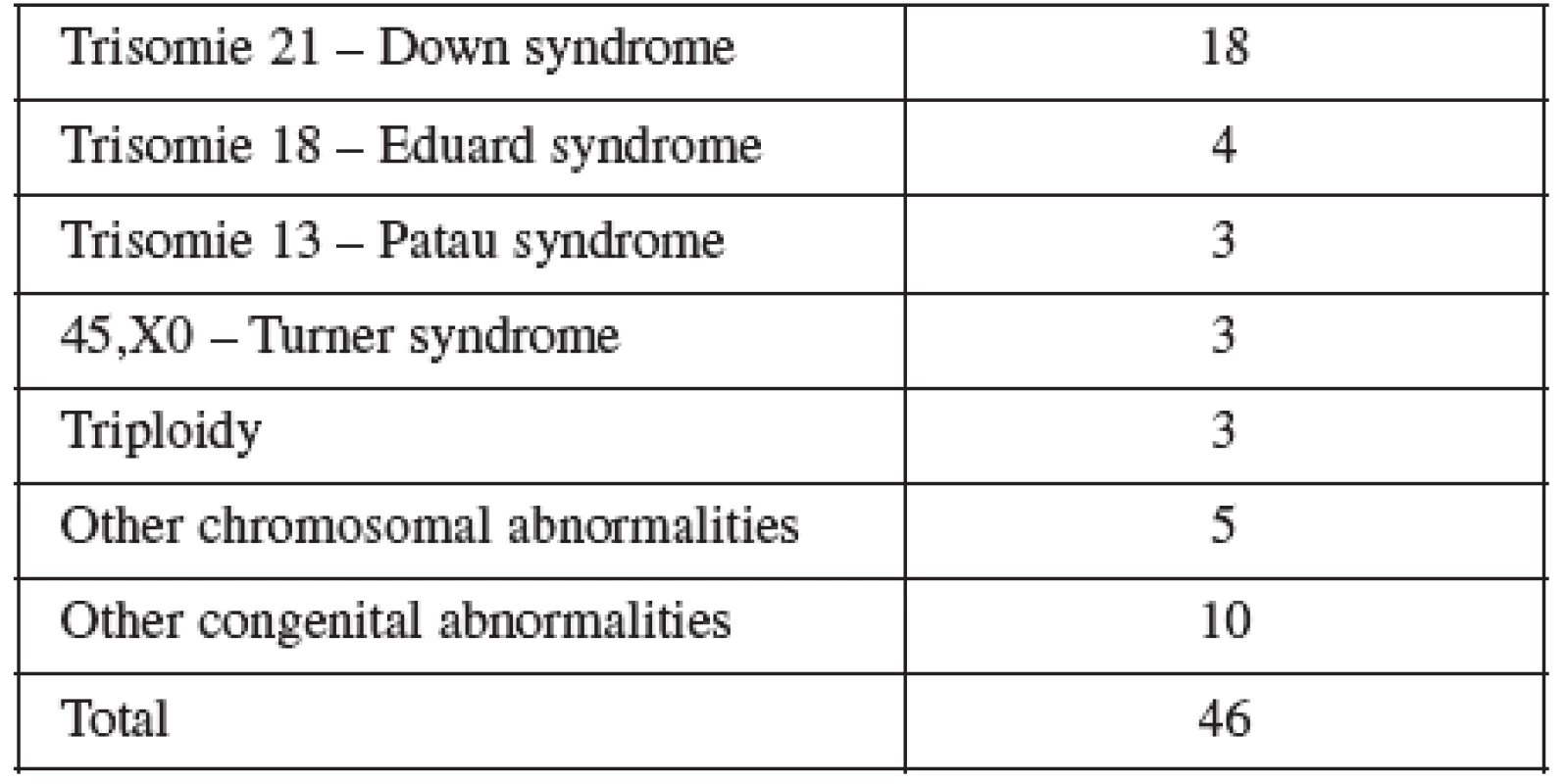

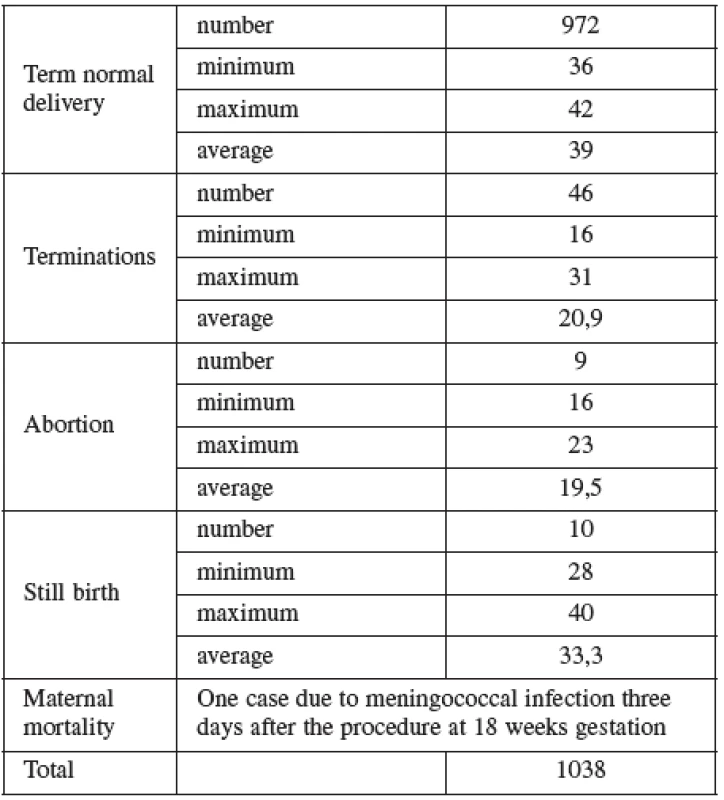

Normal term delivery occurred in 972 cases, 46 cases were terminated for abnormal karyotyp or other abnormality (Table 6), 10 cases of stillbirth and one case of maternal mortality were recorded. The 9 losses considered to be the result of the procedure occurred in two cases at the16th, four at the 19 th, two at the22nd and one case at the 23rd gestational week of pregnancy. Fetal loss rate for this procedure in our cohort was 0.8%. Table 7 shows detailed follow up.

DISCUSSION

The literature focusing on the safety of ultrasound in pregnancy is scant relative to its widespread use and acceptance. In its last publication (2009) the World Health Organization International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology concluded that ultrasound in pregnancy was not associated with adverse maternal or perinatal outcome, impaired physical or neurological development, increased risk for malignancy in childhood, subnormal intellectual performance or mental diseases. According to the available evidence, exposure to diagnostic ultrasonography during pregnancy appears to be safe. The publication points out that due the limitation of studies on some factors (gestational age, duration and number of exposure) the patient should be exposed to the least ultrasound energy necessary to obtain diagnostic information [12, 13].

Most of the available data focusing on amniocentesis and CVS are derived from studies conducted in the 1980s. Several recent studies concluded that the miscarriage risk following the two procedures is comparable and is around 1%, our results are even less. We are aware that the rate of loss to follow up and/or small sample size could skew our results.

Acknowledgments

We thank the medical students Miss Andrea Frantisova and Miss Veronika Durdova from the Palacky University Medical School for their effort and hard work in collecting the data.

Ishraq Dhaifalah, MD, Ph.D.

Department of Medical Genetic and Fetal Medicine

University Hospital

I. P. Pavlova 6

557 52 Olomouc

e-mail: ishraq.dhaifalah@gmail.com

Sources

1. Afirevic, Y., Sundberg, K., Brgham, S. Amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling for prenatal diagnosis. Cochrane Databasee Syst Rev 2003;3:CD003252.

2. Alfirevic, Z., Gosden, C., Neilson, J. Chorion villus sampling versus amniocentesis for prenatal diagnosis. In The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2000 Update Software, Oxford.

3. Barnett, SB., Ter Haar, GR., Ziskin, MC., et al. International recommendations and guidelines for the safe use of diagnostic ultrasound in medicine. Ultrasound Med Biol, 2000, 26, p. 355–366.

4. Brambati, B., Lanzani, A., Tului, L. Transabdominal and transcervical chorionic villus sampling: efficiency and risk evaluation of 2,411 cases. Am J Med Genet,1990, 35, p. 160–164.

5. Brambati, B. Genetic diagnosis through chorionic villus sampling. In Milunsky, A (ed.) Genetic disorders and the fetus: Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. Baltimore, MD, USA: University Press, 1992.

6. Copel, J., Bahado-Singh, RO. Prenatal screening for Down’s syndrome, a search for the family’s values. N Engl J Med, 1999, 341, p. 521–522.

7. Lippman, A., Tomkins, DJ., Shime, J., Hamerton, JL. Canadian multicentre randomized clinical trial of chorion villus sampling and amniocentesis. Prenat Diag, 12, p. 385–408.

8. Miller, MW., Brayman, AA., Abramowicz, JS. Obstetric ultrasonography: a biophysical consideration of patient safety the rules. have changed. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1998, 179, p. 241–254.

9. Mujezinovic, F., Alfirevic, Z. Procedure-related complications of amniocentesis and chorionic villous sampling: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol, 2007, 110(3), p. 687–694.

10. NICHHD (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development) Study Group 1976. Midtrimester amniocentesis for prenatal diagnosis. Safety and accuracy. J Amer Med Assoc, 236, p. 1471–1476.

11. Silver, RK., MacGregor, SN., Sholl, JS., et al. An evaluation of the chorionic villus sampling learning curve. Amer J Obstet Gynecol, 1990, 163, p. 917–922.

12. Tabor, A., Vestergaard, CH., Lidegaard, R. Fetal loss rate after chorionic villous sampling and amniocentesis: an 11-year national registry study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 2009, 34(1), p. 19–24.

13. Torloni, MR., Vedmedovska, N., Merialdi, M., et al. Safety of ultrasonography in pregnancy: WHO systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. ISUOG-WHO Fetal Growth Study Group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 2009, 33(5), p. 599–608.

Labels

Paediatric gynaecology Gynaecology and obstetrics Reproduction medicineArticle was published in

Czech Gynaecology

2012 Issue 3

Most read in this issue

- Impact of oxidative stress on male infertility

- Peripartal hysterectomy – review

- The influence of maternal age, parity, gestational age and birth weight on fetomaternal haemorrhage during spontaneous delivery

- Sever bleeding one year after a cesarean section caused by placenta increta persistens